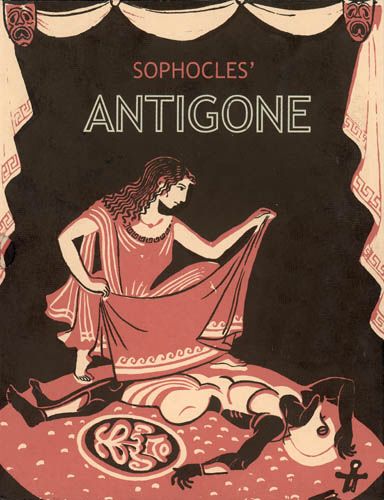

The second half of my programme notes on Sophocles’ Antigone:

The individual against the state

Perhaps the most obvious, and simplest, interpretation is to read the character of Antigone as the voice of individual freedom and conscience. Recalling such modern heroes as Pastor Niemöller, Nelson Mandela, and the unknown man in Tiananmen Square, she unwaveringly does the right thing, no matter what the personal cost, in defiance of the violent and overbearing power of the state as personified by Creon. This reading casts Antigone plainly as the hero, and Creon the villain of the piece, and has much resonance in the context of modern history.

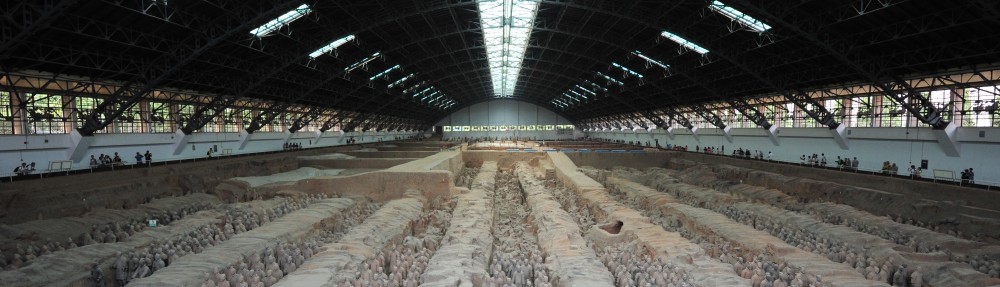

The individual/family against the community

But, to the ancient Athenians, the idea of “the state” as an institution standing over and against its citizens was entirely alien. Athens was a radical, direct democracy in which the citizen body made all day-to-day decisions and in a profound sense was the state. This points the way to a subtler reading, in which the royal princess Antigone stands for the old aristocratic values of hearth and kin, against the needs of the community (as expressed through Creon) to justly punish treason. Creon, indeed, consistently expresses what to a 5th century BCE Athenian audience were sound patriotic values (“as for anyone who holds his own kin more important than his own country, I call that man beneath contempt”), and it is not obvious that such an audience would see him as unequivocally villainous. Creon stands for order in the face of the horrors of civil war and the violent sack of a city – horrors familiar to us from our TV screens, but familiar to all Athenians from direct personal experience. It is this reading that exerted such fascination on German idealist philosophers – particularly Hegel, whose treatment of Antigone in his Phenomenology of Mind sees the force of the tragedy as deriving precisely from the fact that both sides are right, but refuse to compromise in asserting their position.

Religion against politics

Antigone’s actions are driven by the overwhelming religious imperative to carry out the correct, divinely-sanctioned funerary rites over her brother. This reading casts an opposition between this divine law and the man-made political law which Creon attempts to enforce, and asks: which is the higher? This takes us back to Antigone as the paradigm of civil disobedience, appealing to the higher law of the gods to justify breaking the civil laws of men (“it was not Zeus who made this proclamation”); but it also allows us to read Creon as a proto-humanist, ready to contemplate defying superstition and the priesthood in the interests of the human community. Both positions were tenable in 5th century Athenian thought – a time of unprecedented and radical intellectual ferment in which everything on heaven and earth was open to question. Although the action of the play appears to show that Antigone was “right” about the divine will, the gods remain a distant and enigmatic force throughout: there is no deus ex machina to save Antigone from her fate.

Tyranny against democracy

Although the play is set in ancient, mythical Thebes, the political issues are unmistakably those of 5th century Athens. On the one hand, the autocratic, tyrannical Creon, who rules by command and whose favourite metaphors for political leadership are the iron-worker and the horse-tamer, bending a recalcitrant people to his will; on the other, the democratic philosophy espoused by his son Haemon (“A city is not there for the sake of one man”). Ancient Athenian political ideology knew no greater evil than tyranny, and in the play it is the rigidity and unflexibility of the tyrant that brings ruin on both himself and on his city.

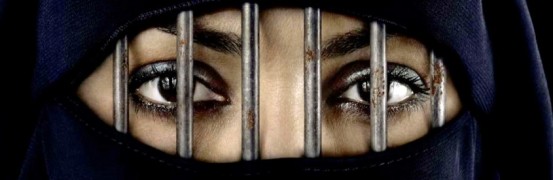

Woman against man

Ancient Athens was a profoundly patriarchal society. Women were excluded from almost all public and political roles – including performing in and (probably – we don’t know for sure) even attending, the theatre. Gender conflict is explicit in the play, and we can read Antigone as issuing a potent challenge to male power. This is what Creon fears the most – if he gives in, Antigone will (in modern idiom) be the one “wearing the trousers”. But can we see Antigone as a feminist hero before her time? Her allegiance is to a divine law that channels female activity into the family and allocates women the primary duty to care for the bodies of their men, even after death. Indeed, the burial of their menfolk was almost the only public role that ancient Athens allowed its women. Antigone does not call for the overthrow of patriarchy – she is demanding to be allowed to finish her household chores.

Pingback: Sophocles, Antigone, and Athenian tragedy | The Rational Colonel