These are programme notes I wrote for a school production of Antigone:

The historical origins of Athenian tragedy are forever lost to us, but the Greek word “tragedy” (“goat-singers”) gives us a clue that it originated out of choral singing and dancing at sacrificial rituals. Give the chorus-leader a separate part to sing against his chorus, and later add a second and a third individual actor – and you have drama as we would recognise it today.

By Sophocles’ day (the fifth century BCE), tragedy was central to the life of the city-state of Athens in a way that is hard to imagine today. Performances were the centrepiece of the Panathenaic festival, a colossal combination of religious carnival with a celebration of the Athenian state – think Christmas and the Fourth of July rolled into one. Tragedy was thus itself a religious ritual, but one played out in front of enormous crowds (the open-air Theatre of Dionysus could seat approximately 15,000) within the framework of a keenly-fought competition between playwrights to win the annual prize – as prestigious as sporting victory in the ancient Olympics.

Tragedy should be understood as a central part of the remarkable intellectual ferment and innovation of classical Athens, which saw the establishment of critical philosophical and historical thought, alongside radical political democracy and the root-and-branch questioning of traditional beliefs. Such philosophical and political questions often surface within the canon of Athenian tragedy. But we should not paint an overly rosy picture of the Athenian golden age – this was a brutally imperialist state, in which war was an almost constant condition of life for all citizens; it was an utterly male-dominated world, which kept its women veiled, secluded, and excluded from the public sphere, effectively the possessions of their male relatives; it was a world where chattel slavery, the ownership of human beings as “animated tools” (in Aristotle’s formulation) was the unquestioned basis of social life. All of these points are relevant to understanding Sophocles’ Antigone.

Our knowledge of Athenian tragedy is slender indeed. Only seven plays of Sophocles, out of 123 he is known to have written, have survived the ravages of the intervening 2500 years. Moreover, all we have is the words on the page. The totality of the spectacle of a performance – the movement, the music, the dance, the costumes, the scenery, the techniques of the actors, the role of the audience – can only be guessed at from the scantiest of evidence.

Yet we know enough to understand the main conventions of the genre. Tragedy was characterised by a high seriousness of tone, language, and subject matter, almost invariably set in the mythical past among traditional legends – in the case of Antigone, the “Theban cycle” of tales about Oedipus and his descendants. The characters and stories of tragedy would thus be familiar to the audience, but there was vast scope for the introduction of rich and fresh material within the context of the familiar. In fact, it is likely that the story of Antigone was largely invented and popularised by Sophocles himself.

Tragedies were invariably presented within trilogies of three tragic plays, telling a connected story. Antigone was the third play in a trilogy of which the other two parts are now lost, but which presumably told the story of Oedipus and his fall (it is a common misconception that Sophocles’ Oedipus the Tyrant [Oedipus Rex] and Oedipus at Kolonos form a trilogy, but they were in fact written for separate competitions, many years apart). In fact, we possess only one complete Athenian trilogy (the Oresteia of Aeschylus). All three plays of a trilogy would play on a single day of the dramatic festival – and, remarkably, “for one night only”. There were no repeats, re-runs, revivals of the classics, or tours of the provinces.

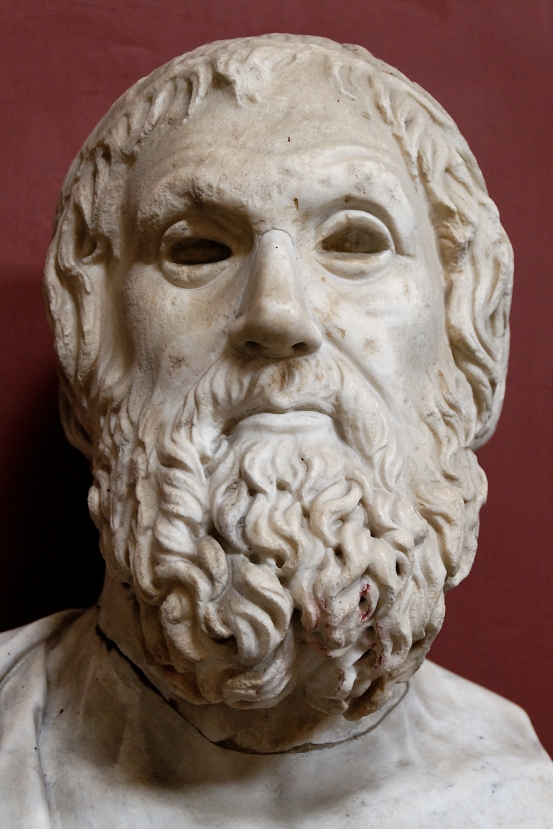

Sophocles was acknowledged in antiquity as one of the three great masters of the tragic stage, along with Aeschylus and Euripides, and won first prize at the annual Panathenaic festival on 24 occasions. However, we know almost nothing about his life. He lived approximately from 495 to 405 BC, spanning almost exactly the greatest years of Athenian power and culture. We know that he held high political office and served as a general in the Athenian army – but this does not make him a “politican” or a “soldier”. The radical Athenian democracy required all of its citizens to be ready and able to serve the state in any capacity.

Sophocles’ Antigone was presented, as part of its now-lost trilogy, at the dramatic festival of 442 BCE. One of the ancient introductions to the play claims that “Sophocles was awarded a generalship in the war against Samos, because of the fame he acquired in staging Antigone”. This may or may not be true, but it still tells us something about the prestige enjoyed by Athenian playwrights, and about the popularity of Antigone in ancient times. It has, ever since, been universally regarded as a masterpiece that has lost no relevance or immediacy across the gulf of 2500 years.

Continued here: What is Antigone about?

Pingback: What is Antigone about? | The Rational Colonel

Pingback: Task 1 – Foundations and Development of Theatre – Tom Jones F16